LocalFood: The Final Course

April 17, 2017

To all my LocalFood friends & followers,

After ten beautiful years on this delicious adventure with you, it’s time to say goodbye to the LocalFood blog. What began as a weekend road trip (reviewing little gem restaurants and eating!) grew into a decade-long joy ride of inspiration, discoveries, and lessons about local food and the people who create it. You’ve helped me learn that there is more to food than nutrition. Good food also provides livelihoods, community, culture and fun. I hope you will follow me over to my new blog on my new website at juliefmorris.com where I have debuted my first novel, Exit Strategy, and will continue to write both fiction and non-fiction. I will keep all my posts from the past decade (!) here, archived and available to read.

Thank you for joining me on this journey and …

Bon Appetit!

xo, Julie

Exit Strategy

April 7, 2017

“A crisis is a terrible thing to waste.”

~ Economist Paul Romer

I started working at a large produce company in April, 2005. My job was to assist the CEO with presentations, government relations and internal communications. I loved it. I advocated for healthy food policy on the national level, met interesting people in the organic agriculture world, and learned how our food is processed from farm to table. That all changed on September 14, 2006 when we found ourselves at the center of one of the largest foodborne illness outbreaks ever. E.coli-contaminated spinach, packed at one of our facilities in San Juan Bautista, California, had sickened hundreds of people across the country and killed three. Literally overnight, my job went from communicating the benefits of eating organic salads to helping coordinate a federal investigation between growers, scientists, investigators, lawyers, insurance agents and victims. For the next four years, I waded through lawsuits and assisted with the attempted sale of the company three times. The third time, the deal actually went through. The family-owned company that celebrated high morale, profit-sharing and innovation was unrecognizable by the time I left in 2010.

Exit Strategy is my first novel and is based on the E.coli crisis of 2006. It is a fictional account, but the themes could be taken from today’s headlines: income inequality, sexual harassment in the workplace, and immigration issues all circulate as a company struggles with its identity and future. Available in both print and eBook, I hope you will support me by buying a copy for yourself, a friend or family member, donate a copy to a local library and/ or request your local bookstore to carry it.

Below, I have listed five easy ways you can help me spread the word about Exit Strategy. (Shout out to Pieces of Me Author Lisbeth Meredith for these tips.) If you’ve already done any, or all, of these, I can’t thank you enough. If you haven’t had the opportunity yet, I would be so grateful if you’re inclined to support me. Thank you!

How you can help support Exit Strategy:

1. SOCIAL MEDIA: LIKE my page on Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/juliefiniganmorris), follow me on Instagram (@finimo), and share news about the book via social media (tag me when you do, so I can thank you, and please be patient while I catch up with thank you’s!) Also, feel free to join the conversation by using the hashtag #exitstrategy when posting.

2. BUY THE BOOK: Please consider buying the book! The first few months it’s on sale are VERY important for a new book release. You can order it through your local bookstore, direct from my publisher Author House, at Barnes and Noble (online or in person), and through Amazon. All of these links can be found on my website: http://juliefmorris.com

3. REVIEW: After you’ve read the book, post a review/rating of the book on Amazon. Reviews will help potential readers decide whether or not to buy the book, and the more reviews, the better.

4. GOODREADS: Add Exit Strategy: A Novel to your shelf on Goodreads and rate it honestly.

5. FOLLOW ME FOR INFO ON READINGS & EVENTS, OR SET AN EVENT UP YOURSELF: Join me at one of my upcoming events, and keep an eye on my website for more updates at http://juliefmorris.com Also feel free to schedule your own event, I would be honored to speak or do a book signing for your group. You can contact me via my website at https://juliefmorris.com/contact/ From civic groups to fundraisers, book groups, faith communities, the possibilities to connect in person or via Skype are endless.

Whatever you decide to do, how big or small, it helps and it means so much. Thank you for your continued support and encouragement, and please let me know how I can pay it forward.

Thank you so much,

Julie Finigan Morris

A Letter to Lucky

November 20, 2015

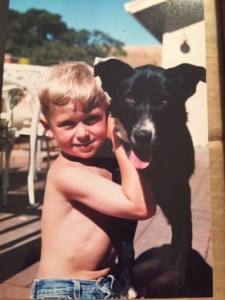

For farm and ranch families, pets are more than companions. They work hard and play an important role in the business. Cats hunt mice around the house and barn. Dogs work cattle and are invaluable during gathering and shipping season when the cowboys need to move herds of livestock. This post is a tribute to our Border Collie/McNab, Lucky.

A Letter to Lucky

Oh how I remember your arrival Lucky! Greeted with hugs and squeals of joy on Christmas Day. Santa hid you in the horse trailer, the grand prize of our early morning treasure hunt. Jack was five. You and he would roll around together for the next 13 years, exploring the ranch and working cattle. What a perfect pair.

Jack left for college in August, maybe that’s when you decided your most important job was done. You hung on for the next four months, maybe to ease my transition into an empty nest. Thank you for that gift. I will miss your shadow, following me up the stairs to my office and sitting at my feet while I write. Running with me – more like trotting behind lately, still determined to join me – on the road beyond our driveway. Raiding the cat food when you thought I couldn’t hear your tags clanking the side of the dish. Sometimes I think you were just being mischievous for the hell of it. Completely deaf, you still saw chatty walkers along the road and barked, protecting me from the unfamiliar. You showed the same protection for your puppies, safe and well fed in your care: Vern, Fini, Mo, Abbey, Jude, Skunk and their siblings. Octomom had nothing on you.

Thank you for training the other dogs how to gently move a hundred plus head of cattle, always attentive to the bosses’ commands: “Go left, Lucky. Go around. Bring ’em on, girl. Stay. That’ll do. Good girl, Lucky, good girl!” Joe says you were amazing in your heyday, sensitive yet strong. I still see you sitting up on the hill, watching for a stray and gently bringing her back to the herd. You did the same if a toddler wandered from the group, always a good mama. When your breathing is labored and your hind legs weak, I know you are ready, even if I am not. You are ready for rest. Ready for peace. I’ve dug a grave for you by the frog pond, just across the creek bed near the road. The soil was soft after the first rain of the season, welcoming you back to the earth. The birds will sing for you and an old oak tree will shelter you. I will remember you as I run by each day, missing you and knowing that I was the lucky one.

What is Soil Health Food?

November 12, 2015

I recently watched Cowspiracy: The Sustainability Secret, a 2014 documentary about animal agriculture. Filmmakers Kip Anderson and Keegan Kuhn point to animal agriculture as “the most destructive industry facing the planet today.” They are incredulous that leading environmental groups such as the Sierra Club, Surfrider Foundation and Food & Water Watch do not speak out more forcibly against animal agriculture. The film implies there is a conspiracy – nod to clever title – to hide the impact of animal agriculture on global warming.

Veganism advocate Leonardo Dicaprio wears leather jackets and uses hair gel, most likely made from cow byproducts.

I admire Anderson and Kuhn’s passion about climate change and their work to raise awareness about its causes. They did exhaustive research and interviewed a list of academics, authors and scientists to support their premise. Their numbers are staggering. I won’t repeat them here, you can refer to their infographic here. But their statistics are skewed to advocate their agenda against animal agriculture. They ignore data that doesn’t support their opinion, such as this Global Warming Flow Chart from the respected and unbiased World Resources Institute and in a classic case of propaganda, the interviews with experts are heavily edited and out of context. Of course industrial feedlots have negative consequences on our environment, but that’s not the only type of animal agriculture. The film also points to fisheries, grassfed beef, and even organic, urban farms that rely on cattle manure for fertilizer as harmful practices for the planet. They really don’t like animal agriculture. Their conclusion is that veganism is the solution. They have chosen the cow as their scapegoat in the larger, and systemic, problem of climate change.

Cattle are not the problem, humans’ poor management of them is. Animals have a crucial role in a healthy carbon cycle, turning and fertilizing the soil with the every step. They just need to be managed, on rangelands where they belong. Meat is simply a byproduct. Even the most serious vegans probably use animal parts in other areas of their lives. Do they drive cars? Tires come from stearic acid, a cow by-product. Roads are built with a beef-based fat that makes asphalt. Household products such as candles, cosmetics, crayons, perfume, mouthwash, toothpaste, shaving cream, soap and deodorants are all made with fatty acids and protein meals from cows. Cattle also produce hundreds of life-improving medicines. “More than 100 individual drugs performing such important and varied functions as helping to make childbirth safer, settling an upset stomach, preventing blood clots in the circulatory system, controlling anemia, relieving some symptoms of hay fever and asthma, and helping babies digest milk include beef by-products. Insulin, for example, is produced using cow pancreas. Additionally, gelatin capsules are commonly used for a variety of medications,” according to environmental site One Green Planet. Leonardo Dicaprio, one of Cowspiracy’s major funders, wears leather jackets and travels on private jets. One flight across the U.S. on a private jet releases as much carbon on the atmosphere as an average American does in a whole year.

Rather than taking a single issue, vilifying it as THE problem and trying to solve it, we should be focused on the whole system and ask ourselves what we can do to make it function better? Veganism will not eliminate dead zones in the Gulf of Mexico. In fact much of those are the result of nitrogen fertilizers flowing from soybean (read: tofu, fake meat) and corn monocrops covering the Midwest. Corn and soy crops reported record production levels in 2014, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Nor does veganism solve the problems of deforestation or desertification, also symptoms of poor land management. Palm oil farming takes out rain forests too. Soybean fields blanketing the Midwest and the bare soil – soil loss – associated with large-scale vegetable monocultures have their own massive environmental consequences. Veganism fails to address the issue of how to manage millions of acres of rangeland unfit to farm other crops. If we are to slow, stop, and ultimately reverse climate change, we need to use systems thinking and look to processes, preferably modeling the most brilliant process of all: Mother Nature’s carbon cycle.

The Soil Carbon Coalition is helping people shift from a problem-solving orientation to a creative one, focused on the solar power of the biosphere.

Soil Carbon Coalition Founder Peter Donovan suggests “covering the land with green, photosynthesizing plants.” He calls soil carbon “the most powerful and creative planetary force.” Rangelands provide an enormous opportunity to produce soil carbon and animals are Mother Nature’s way of turning, fertilizing, and “covering the land with green, photosynthesis producing plants.” (They also use no fossil fuel to operate.) Meat is simply a byproduct of animals, our partner in a well functioning carbon cycle. Maybe the reason Sierra Club, Surfrider Foundation and Food & Water Watch aren’t looking solely to animal agriculture is that they are trying to look at the whole system. Ask yourself this the next time someone offers you a tofu burger or fake egg made of yellow peas: Does this food enhance soil health? Is it beneficial to the carbon cycle? How was it produced? Am I supporting what I want for the planet when I buy it? If it’s not, you may want to re-consider. It’s not the type of food one eats that will determine the future, it’s how it was produced. I call it “Soil Health Food.” A locally-grown, grassfed burger that comes from a cow who nurtured a plant that helps capture and store carbon where it belongs, deep in the soil beneath our feet, may not be such a bad choice after all.

First Person Certified, Part II

April 24, 2015

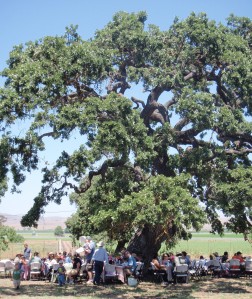

I first wrote about first person certified food back in 2010, inspired at one of our field days by all of you: our customers. I was responding to a question about whether or not we were certified organic. My response: “We’re first person certified.” I had just returned from a trip to Washington D.C. where I was lobbying for healthier school lunches as part of my job at one of the nation’s largest organic food companies. It occurred to me, right there in front of 100 of our customers gathering around tables for a slow lunch on the ranch, that relationships we were building were more important than a third-party approval from politicians on the other side of the country. (I’m still in favor of healthier school lunches, sourced from local farms and ranches.)

A food producer can’t pay to be first-person certified. You either are or you aren’t. It’s up to our customers to decide – you are our auditors and if we don’t pass your inspection, we’ve just lost a sale. Another issue with organic standards is that they were written for produce. They don’t even apply to grassfed meat production. Our own standards require that cattle are raised and finished on green grass, in open pastures and moved often to prevent overgrazing.

Organic became an issue in the 1970s and 80s in response to farmers who used the term “organic” but were spraying pesticides. Those growers who actually did follow organic practices wanted to differentiate themselves so they established a set of standards, eventually passed as the Organic Foods Production Act of 1990. The rules regulated everything from what growers could put into the soil to how crops are harvested & washed. The rules do nothing to address problems with conventional meat production. (What modifications have been made came later and were heavily influenced by the conventional meat industry: the same folks who actively work against grassfed beef producers.)

Although the dairy industry has modified organic standards to be specific to its operations, prohibiting the growth hormone BST in milk and mandating that cows at least have a view of the outdoors, the beef industry has largely tried to apply the USDA national organic standards developed for produce to its own operations, a pitiful attempt at capitalizing on the marketing value of “organic” with little attention to the health of land, animals or people. A single organic certified hamburger, for example, can be made up of ground beef from more than 100 different cows, confined in a feedlot and fed grain as long as it’s made from organic corn. Big deal. It does nothing to improve our soils, the animals’ lives, or our own health. We do not use any synthetic additives, even if they are approved organic. None of these requirements are part of the USDA’s organic standards for meat. To put time, effort and money into a certification that does not meet our own high standards is not only bad policy, it’s counterproductive to our goals of healthy rangelands, animals and people.

Our friend Douglas Gayeton of the Lexicon of Sustainability describes it this way:

Local – “Local brings you back into a relationship with the source of your food, with the land, the animals, the plants, the farmers, and with each other.”

–LOCAL: The New Face of Food and Farming in America, by Douglas Gayeton

Organic –“A labeling term that indicates that the food or other agricultural product has been produced through approved methods that integrate cultural, biological, and mechanical practices that foster cycling of resources, promote ecological balance, and conserve biodiversity. Synthetic fertilizers, sewage sludge, irradiation, and genetic engineering may not be used.”

– according to the USDA’s National Organic Program (NOP)

Local Food System – “A regional food system is one that supports long-term connections between farmers and consumers while meeting the economic, social and health and environmental needs of communities in a region. A food system includes everything associated with growing, processing, storing, distributing, transporting and selling food. A food system is local when it allows food producers and their customers to interact face-to-face; regional systems serve larger geographical areas, often within a state or metro area.”

-Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture

Face certification – “A direct contact between farmer and consumer that creates an environment for trust and faith.”

–LOCAL: The New Face of Food and Farming in America, by Douglas Gayeton

In a previous post titled Think Big. Be Informed. I described my six years in the organic food industry, an eye-opening experience that taught me the difference between Big Organic and local food. If you care about the long-term connections between farmers and consumers and/or the economic and social impacts of your food purchases, it comes down to two, simple questions: Who made this food? and How was it produced?

Organic certification does not require that a company pay its workers a living wage or support its local community, but first person certification mandates it. I was thrilled to learn recently that the large organic produce company I lobbied for, based here in San Benito County, has joined the board of our local Chamber of Commerce, after 25 years in the community. Management is creating an environment for trust and faith in the community where the majority of their employees live, a great step toward becoming first person certified. And they don’t even need to pay for it.

Local food: London style

March 17, 2015

Across the pond this week, in London where there is no shortage of good food. We went to Borough Market yesterday: a feast for every sense. Bustling with artisan vendors, office workers grabbing a quick lunch, and chefs picking up ingredients for their restaurants, the outdoor marketplace has been a central part of the London foodie scene since the 13th century.

What I love is the international celebration of food that is produced close to home and on a small scale: there are no industrial farming practices seen in this place. Signage on most vendors booths pays homage to food raised slowly and without chemicals or inhumane treatment. Methods are explained in detail to curious tourists asking questions about everything from how long the perfect Parmesan cheese is aged to the best way to cut meat from the bone, I’ll let the pictures do the talking from here. As you see the sights: be sure to imagine the accompanying sounds of enthusiastic vendors encouraging you to try a sample, aromas of warm paella, and feel of 600 year-old cobblestones under feet.

Mixing it up at TomKat Ranch

October 21, 2014

What do you get when you mix together innovators, entrepreneurs, farmers & ranchers? Great ideas that are already helping to change the landscape of local food production and consumption in California.

The Pescadero Idea Hack, held in Pescadero, Calif. on October 11, 2014, was the brainchild of The Mixing Bowl Hub’s Rob Trice and his wife, TomKat Ranch Executive Director Wendy Millet. Millet and her amazing team at the TomKat Ranch are our partners in the push to make grassfed beef the new normal. Like Morris Grassfed, TomKat Ranch is committed to considering the land, animals and people when producing its LeftCoast Grassfed beef and has worked hard to increase local, grassfed beef consumption in schools and restaurants in San Mateo County.

We started the day with introductions and it was humbling to be a in a room (a barn, actually) with so many people dedicated to producing good food and creating local markets that encourage and reward the work of farmers and ranchers.

“Our objective is to build upon numerous assessments and dialogues on the topic of the Peninsula’s local food production, and develop a range of actionable solutions. A byproduct of the Idea Hack is to connect individuals and organizations that could potentially collaborate to bring about desired changes,” Trice said in his opening remarks.

Participants like Karen Liebowitz, co-founder of the soon-to-open The Perennial restaurant in San Francisco and Pete Hartigan, Founder & CEO of Trusted Ventures, LLC are not only innovative thinkers, but agents for social change. Liebowitz’s new restaurant will source foods from local farms and ranches that go way beyond industrial, monocrop organics; they actively address climate change with their farming practices.

“We first started thinking about what can we do to engage with our environment more closely — not just farm to table, but really deeply engage,” Liebowitz said in a recent interview with the San Francisco Chronicle. The Perennial will be a “laboratory,” in which all aspects of the restaurant’s business — relationships with farmers, sustainable practices, choice of vendors — are seen through the lens of environmental impact, the article said.

Hartigan has put his money where his heart is. The founder of several successful start-ups, his latest is Trusted Ventures, LLC which aims to develop what he calls the “Impact 500” targeting existing Fortune 500 cash flows in areas like finance, healthcare and education, with a model where helping the community is how the company competes versus the traditional maximize shareholder profit model. If this sounds familiar, it’s because Hartigan has already created successful companies using the model, including the alumni-funded college loan business sofi.com, which he plans to take public this Spring. He’s not wasting any time on his next project ether. Our breakout group’s challenge: How Can We Increase the Amount of Local Food Consumed by Local Institutions?

After an hour-long discussion with institutional food buyers (Stanford and Google), distributors, farmers and ranchers we developed the “LOCAL FOOD MARKETPLACE, INC.” (LFM). Our idea is to develop a collaborative, digital market maker, facilitator/coordinator. LFM can create a demand book for local institutions looking to buy local food supply and aggregate local supply. To pay the premium for fairly priced local goods, dining services organizations can supplement their budget through HR budgets (since employee good food eating should result in lower health costs) or a company’s community social responsibility funding. Financial institutions with a social mission can finance working capital for growers. Participating growers can have an ownership stake in LFM’s success. (We won First Place, by the way.) Bam.

Other challenges included: How to train and support the next generation of farmers and ranchers? How to scale local food production? and How to deepen the connection between SF Peninsula eaters and growers? We took a hike on the spectacular TomKat ranch after our breakout sessions and capped the day with a candlelight dinner around the ranch’s coi pond table: a stunning setting and perfect way to celebrate the beauty and bounty of local food. The Mixing Bowl plans several follow-up sessions and has started discussion groups for each idea we came up with. The real success here is the awareness that good, local food is not only delicious, it’s a force for economic, social and ecological good.

How much water does it take to make our favorite foods?

September 8, 2014

This post originally appeared in the monthly newsletter of Morris Grassfed Beef. It has been modified for localfood.wordpress.com. To sign up for our monthly newsletter, click here.

We often hear about the large amount of water it takes to raise cattle. The numbers are huge but almost always simplistic. No doubt, a cow needs water to thrive, but we don’t see Morris Grassfed Beef as a detriment to the water cycle. In fact, we think Morris Grassfed Beef actually enhances the water cycle by producing healthy rangelands that capture and hold clean water, which then flows to the ocean and surrounding community. The question is not so much “How much water does it take to raise beef?”, but rather “Is the beef you are purchasing helping to slow down the water cycle or speeding it up?” Our goal is to slow the water cycle down, capturing and storing this precious resource where it can nurture the soil.

Our cattle drink from natural springs and creeks, filled by rainfall (when we have it!) and consume approximately 10 gallons a day, per cow. (We had to haul water from the best producing springs to the herd in the Fall/Winter of 2013/2014, for there was no other water on the ranch, so we know exactly how much the cows were drinking.) That’s 3,650 gallons per cow, per year. It takes about two years to raise a cow, totaling 7,300 gallons. Divide that amount by the pounds of beef produced from a single Morris Grassfed cow, approx. 360, and you get 20.28 gallons of water needed to produce one pound of Morris Grassfed Beef (or 6.76 gal. for a 1/3 lb. burger). Our abattoir and butchers also use water to wash the carcasses and clean their facilities, which we factored in to our final calculation of 7 seven gallons per burger.

The average family of four uses approximately 360 gallons of water a day.* That’s 131,400 gallons a year, or 36 times what a cow uses. Granted, cows are not flushing toilets, taking showers or watering lawns … at least not with tap water, but it puts into perspective how much water daily life takes. Let’s compare how much water it takes to make a glass of wine, a cup of coffee, a head of lettuce and a conventionally raised pound of beef vs. grassfed. (We should note that finding reliable numbers for these things is difficult. Many of the sources that come up are ideological and have an ideological agenda to push. We tried to find the most un-biased, scientific evidence we could. And we know our numbers are correct because we monitor and measure them.) The following chart shows the water needed to make each of these popular foods:

Conventionally raised beef takes more water because the cattle are fed water-intensive corn and alfalfa crops, and drink from imported water in feedlots rather than natural springs and creeks. Unfortunately, as soon as cattle are placed in feedlots they can no longer contribute in a beneficial way to the water cycle. Consider also, the number of calories and nutrients each of these foods provide. Although a head of lettuce takes about the same amount of water as a pound of Morris Grassfed, while supplying only about a quarter of the calories, a Morris Grassfed burger packs essential Omega 3 fatty acids, amino acids, and other vitamins and minerals necessary for a healthy brain and body. We love a glass of red wine as much as the next person, but it takes more water to make than your Morris Grassfed hamburger.

Finally, if the more than 4,500 acres of rangeland that are managed by us is improved so that each acre, approximately the size of a football field, captures an extra inch of rainfall that would be an additional 27,166 gallons per acre, a huge net gain by management of Morris Grassfed Beef. This is not at all inconceivable. Your hamburger is a boon to your family’s health, your community and the water cycle. So, the next time someone tells you beef uses too much water, give them our number.

The Wild Wild West of Local Food

July 21, 2014

July is peak season for farmers and ranchers: crops need to be harvested, cattle need to be watered, and product needs to be marketed, packaged and delivered. Seasonal farmers markets are great examples of this annual celebration. For the farmer and rancher, it’s the culmination of months, sometimes years, of inputs.

In our case, a grassfed rib eye is three years in the making, beginning with securing – and paying – the lease for the rangeland. The cattle graze, gestate, nurse, and grow into beautiful two year-old finishing animals. In addition to our own calves, we sometimes purchase animals, called “replacement cows.” Their price is determined on a per pound basis, recently subject to steep increases in the live cattle market. Drought has been a recurring theme around the West for the last decade, and there are simply too few mother cows to raise enough calves to meet the demand from the U.S and around the world. Bulls are also purchased to breed the cows. Upon conception, it is our job to ensure the mother cows have plentiful and nutritious forage to graze and clean water to drink. The calves are born in March and April, nurse for six to nine months and are weaned when the mothers are ready for a break. All this is overseen by the physical labor of cowboys who fix fences, dig pipelines, and tend the animals every day: seven days a week. Mother Nature does not follow a Monday- Friday 9 to 5 schedule.

By fall, calves have grown into young heifers and steers. They are moved often to fresh pasture for their own health and growth and to prevent overgrazing of the plants they eat, leaving behind fresh fertilizer that nourishes the soil and creates deep roots that capture and store carbon. It’s a cycle that has repeated itself for thousands of years, initially in the wild when predators chased large herds of elk and buffalo and now by land managers who mimic those same patterns with electric fences and domesticated cattle. This process produces not only breathtaking landscapes, but nutrient-rich, delicious grassfed beef we distribute to Californians.

The processing side of grassfed beef is less harmonious. We begin talking with butchers in late fall to line up slaughter dates for the following May through September. As small, family owned businesses themselves, our abattoir and butchers need to plan ahead of time as well. They need to hire enough people to adequately and humanely process incoming live animals and carcasses. On our end, we have to time the slaughter dates with perfectly finished animals, the capacity of the butchers, and the needs of our customers. Throw in drought (aka: the need to find irrigated pasture) and a fast growing, competitive local meat market and things get complicated. In short, you can’t expect to call the butcher and tell him you’re bringing in a load of cattle in the morning. Aligning slaughter dates is more like nabbing orchestra section seats at a sold-out Broadway show: it takes a lot of planning, ability to pay the ticket price, and a little bit of good luck.

Once slaughter dates are reserved, we begin to watch the herd carefully, choosing the finished animals each week to be trucked to the abattoir. After the animals are killed, the carcasses are shipped to the butchers who have lined up their own teams to cut and wrap the meat, evenly dividing the steaks, roasts and ground beef into neatly packed boxes ready for delivery. By the time we pick up the boxes at the butcher, it has been between two and three years of work. We have paid our landlords, cattle brokers, ranch hands, supply and hardware stores, vehicle and trailer mechanics, fuel and transportation costs, abattoirs, butchers and cold storage facility. Payday has come for everyone but the rancher. All along the way, the local economy is thriving: a testament to the many benefits of local food.

Then there is delivery day, yet another wild turn on the path from farm to fork. Our typical route starts the day before deliveries when we drive from our ranch in San Juan Bautista, Calif. 300 miles north to the closest USDA-inspected combined butcher/slaughter facility that meets our standards in Orland, Calif. (Joe drove the live animals up a month prior. The carcasses hang to dry-age for three weeks before being cut up.) We arrive in the evening for a good night’s sleep to prepare for a 5 a.m. wake-up call to meet Darren, our butcher, at 6 a.m. and begin loading the trailer. Over the next two days, we work our way south to deliveries in Sacramento, Stockton, Tracy, Pleasanton, Berkeley, San Francisco, San Jose and Gilroy. The second day, we cover the Central Coast: Monterey, Aptos, Scotts Valley, back to San Jose and finally home to Hollister and San Juan Bautista.

Traffic patterns add to the complexity. This month, we were humming along in between stops when we saw the freeway sign: “Traffic Stopped on Hwy 17. Use Alternate Route.” (For those familiar with the Highway 17 corridor between Scotts Valley and San Jose, the “alternate route” is a two-hour detour along Highway 1.) Realizing we were going to be stuck in traffic for hours due to a fatal truck accident and 11-car pile-up, we immediately sent a group text notifying 25 customers in Portola Valley that we’d have to re-schedule their delivery. Sigh. At each stop, we meet customers and collect the balance due, based on a pre-arranged price per pound, minus customers’ $250 deposit, which we collect as “earnest” money and to defray some of the aforementioned costs.

It’s a celebratory day not only because it’s so much fun to meet our customers and know we are filling freezers with amazing healthy food, but also because it is satisfying to know that such a complex process has brought all of us to a community building and happy moment. Still, by the end of Day Three on our delivery route, I am more than ready to pair a glass of local Pinot Noir with one of our filet mignons.

Such is the wild ride of farming and ranching. In most industries, the customer pays for a product that has been developed, manufactured, marketed and delivered according to well-established and set production costs. The seller knows his cost per widget and sets the price accordingly, with a profit built in and collected at the point of sale. In local food production and delivery, the customer pays for a product that has been developed, manufactured, marketed and delivered in the context of a wildly unpredictable relationship with Mother Nature, traffic patterns, and other variables the seller has little control over. The majority of customers understand these complex twists and turns and happily choose to join us on the ride. They leave work to meet us, send in a deposit, tell fellow, waiting customers we’re running late and invite friends over for a BBQ of grassfed hamburgers. One of our customers brings us homemade biscotti to snack on along our delivery route. Another offered to meet us at a later stop this month to exchange her boxes after we realized we gave her someone else’s custom cut order. (Shout outs to Jane and Marsha!) Many jump in and help us carry boxes to cars, or bring extra brown shopping bags for people’s “extras” orders. These are not just “customers” they are our partners. Without them, none of this would work.

As we approach our 25th year producing and marketing local grassfed beef, it’s exciting to see the market exploding. Once considered a trend, grassfed beef has gained respect and popularity among meat lovers, chefs and environmentalists alike, all of whom are up for the wild ride. Hold on, because we don’t see it slowing down anytime soon.